Shop-Girl Delight

Discovering Dorothy Whipple's Unlikely Fairytale

Dorothy Whipple is a name I kept hearing mentioned, and when I posted about women entrepreneurs in fiction, High Wages was mentioned in the comments. By chance, I soon afterwards joined a new library and on my first visit was running my eye along the shelves – a bit like a shopper picking out a new fabric come to think of it – when one of those elegant, grey Persephone covers jumped out at me. It was High Wages. And what a delicious read it is.

(Is “delicious” a subconscious association with raspberry ripple/whipple ice cream? Anyway, it was a treat of a novel.)

High Wages (1930) is set in the period around the First World War, and unusually focuses around the adventures of a shop-girl, Jane Carter. Jane is young, only seventeen when the novel begins in 1912, but has already been working for two years in a small town in Lancashire. Visiting the neighbouring, slightly larger town, she sees a card go up at Chadwick’s: the “best draper’s shop in Tidsley”.

Wanted: a young lady to assist in the shop. Apply within.

She applies, and as she is smart, pretty and well spoken, she gets the job. From there follows six years of toil, during which time she doubles the profits with very little appreciation from her employer, on a wage of five shillings a week plus board (later raised on Jane’s demand) until fate conspires to make her position untenable. At this point she takes the bold step of opening her own shop.

There’s a lot of drabness in Jane’s life: measuring out ribbons for bored customers, cold baths, and cold tripe for supper, provided by her employer’s penny-pinching wife who also shaves the margarine off Jane’s war-time ration to put in her husband’s stew. But there’s also a Cinderella feel to her story: Jane begins as the unappreciated orphan drudge, with a disinterested stepmother and Mr Chadwick and his wife as stand-ins for the Ugly Sisters. They even go to a Ball. (The annual Hospital Ball, essential for raising funds in the pre-NHS era, and the social highlight of Tidsley’s year.) The Ball tickets are provided by Jane’s Fairy Godmother, the kindly Mrs Briggs. In short, High Wages is an enticing mixture of realism and fairytale, but it is powered by Jane’s entrepreneurial drive.

Jane and Jane’s

Jane is wonderfully endearing: eager, clever and passionate, she’s also original. Unlike many contemporary heroines, she does not make her way through education (she was forced to leave school at fifteen) nor through marriage (she is at first wary of men, later unlucky). She loves nature and reading as much as frocks, and lives life with a passionate intensity. Wilfred, the local librarian, provides her with reading matter and Jane responds with her usual enthusiasm:

HG Wells was like wind blowing through her mind. She felt strong and exhilarated after reading him. … He made her want to get up and fight and go on ….

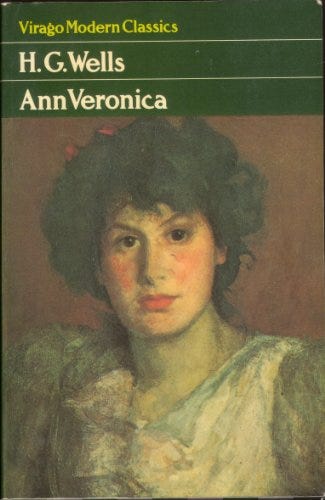

Whipple does not labour the point, but there seem to be coded messages in the books Jane enjoys. As a child she was read David Copperfield and Oliver Twist (books about struggling orphans) and Alice in Wonderland (a sparky girl making her way alone in a world of odd characters). From Tidsley library she reads books like Ann Veronica by HG Wells which feature “New Women” defying expectations (according to the introduction by Jane Brocket, there were many books in this genre by the likes of Wells, Arnold Bennett and George Gissing) but in the case of Ann Veronica anyway, the heroine is middle class and London-based: however aspirational, she must have seemed a distant role model to Jane.

(For some reason, as Harriet explores in this fascinating post on Whipple, the feminist press Virago disdained to reprint Whipple in the 1970s. Most likely, as she suggests, because Whipple was “Middlebrow, Middle-Class, Midlands and Middle-Aged”. They did reprint Wells’s Ann Veronica. Hmm.)

Instead, it is shop life that provides a path forward. There is a magic around shops, I think, even if like me you aren’t necessarily a shopping type. As a small child my most longed for toy was a Toy Sweet Shop, and a friend and I played “shops” in the playground at school. (It was a pet shop, admittedly, not a draper’s shop.) Like many people, I now have fantasies about a bookshop, with a cafe attached, even though I’m well aware how the sector struggles. There are whole literary genres about people setting up tea shops in Cornwall. So Jane is far from alone in her aspirations.

And for Jane, her own shop means everything. Economic independence. Respect. Her own living quarters, including, for the first time, her own bedroom. An escape from cold tripe and kippers. The ability to help friends like Lily the cleaner, as well as her customers. Trips to London, and the chance to make connections there. No wonder she calls her shop, unapologetically, Jane’s.

You know the best of it is–being alone. That’s why I’m so happy. I’ve never been alone–in the daytime–since I can remember. Oh, I am happy. I’ve never been so happy before–and perhaps I shan’t ever be again. My shop, my shop, my adorable shop!

The above is somewhat prophetic, as Jane’s life is increasingly distracted from her adored shop towards romantic entanglements, and in my opinion, the last quarter of the novel and Jane’s life is less satisfactory as a result. (Who could really get that excited about wishy-washy local solicitor Noel Yarde?) It’s a small quibble about such a lovely read, though, and luckily Jane is too strong a character to be subsumed.

Shop Life

One of the joys of High Wages is that it is so completely immersed in a concrete place and time, albeit encapsulated in the fictional “Tidsley”, a Lancashire mill town which I imagine is heavily based on Blackburn where Whipple grew up1. In Tidsley, the day begins at half five in the morning, when the clog-clad inhabitants surge across town on their way to the mill:

Dark shapes streamed across the market-place; clatter, clatter, clatter.

Tidsley depends on cotton, in a region which depends on cotton, but most of the book is focused on the doings in market square where the main shops - Chadwick’s, Fenwick’s (the furrier), The Victoria Cafe and the rest are situated, with the market stalls set up outside. Chadwick’s is a traditional draper’s, selling habberdashery (everything needed for dressmaking), bedding and other fabrics, and a very few ready-made clothes like gloves. The business is sufficient to support Mr and Mrs Chadwick, two assistants and a daily cleaner. Jane and Maggie Pye, the other assistant, both sleep in. (This surprised me, but was apparently still fairly common at this period. Later, retail was attractive to young women precisely because, unlike domestic service, you could go home at night.) Jane and Maggie dust the shop each morning, before dressing in black frocks to greet the customers, usually women, who are brought chairs to sit in while they inspect the merchandise. Most of what is sold in 1912 is then taken to a dressmaker, but the clothing trade is about to shift to “ready-made”: the transition that will fuel Jane’s own career. Thursday is early closing – the day when Jane takes the train to Manchester to look at the famous Kendall’s department store, or has tea with Mrs Briggs, or (disastrously) visits Wilfred, the ‘young man’ of her fellow assistant who works in the Free Library (free, after an initial joining fee of tuppence).

It’s a world in which shopping is stately, slow and ritualised. It has dignity and personal interaction, but it’s also stultifying, and lends itself to petty snobbery, of which Jane is sometimes the victim.

Ups and Downs

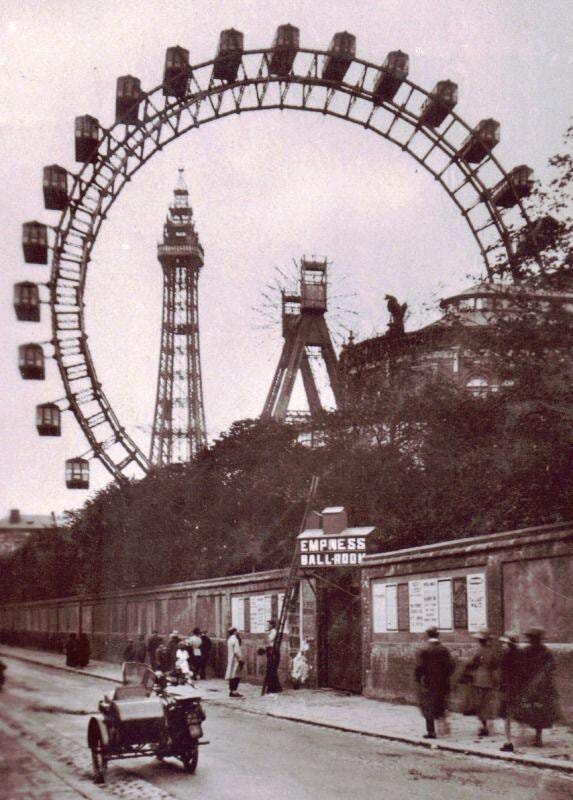

The novel shows how economic change drives an (often reluctant) social mobility. Mrs Greenwood, the obnoxious wife of the mill owner and Mr Chadwick’s most prized customer, lords it over the town and does her best to keep uppity shop owners, like the Chadwicks or Jane, in their place. However, there is nothing she can do when Fenwick, the furrier, buys a house near hers, and she even flirts with Mr Briggs, who has risen from obscurity to become partner in the mill. Meanwhile, Mrs Briggs prefers a humbler life, using only a corner of her grand new house, and relishing the chance of a trip to downmarket Blackpool with Jane. (Mrs Briggs much reminds me of Trollope’s similarly reluctant riser, the endearing Lady Scatcherd.) Mrs Briggs’ cotton fortunes will inadvertently be important to Jane, and later Jane will have a chance to return the favour.

(By the by I really enjoyed Jane and Mrs Briggs’ trip to Blackpool. My grandparents kept a boarding house there.)

The novel also shows the economic changes brought by the 1914-18 War. Mr Chadwick, guided by Jane (while still his assistant) successfully wins contracts for army uniforms and hospital sheeting; although Jane does her very best to stop him profiting from the bereaved. Mr Chadwick is perhaps one of the “hard-faced men” who profit from the war (John Maynard Keynes’s description) although perhaps too ineffectual to truly qualify for the title. When Jane decides to go it alone, he first takes the hump, then tries to lure her to stay, by dangling the prospect of her taking over the business eventually (though he knows perfectly well he will sell it “and retire to St Anne’s”, the more upmarket alternative to Blackpool).

While war brings opportunities, and post war there was a brief boom in Britain, the country was soon pushed into the economic doldrums – at least in the industrial north. In a way the book does show the economic fragility of Tidsley, though through the frailties of the mill owners rather than the wider economic scene. Not that the two were completely unconnected. John Maynard Keynes for a while was embroiled in the affairs of the struggling cotton industry, when he tried to devise a plan to revive the stagnating UK mills in the 1920s. He met mill owners very like Greenwood, the Tidsley owner, and despaired at their lack of interest in innovation and investment, and their determination to cream off any proceeds for themselves. But High Wages ends before unemployment starts to really bite, and transform what had been thriving northern towns. Nevil Shute’s novel Ruined City, although set in the North East, gives a flavour of what could happen when one town was so heavily dependent on one industry.

Even when Tidsley was flourishing there was hardship. Even a “respectable” shop girl like Jane might not get enough to eat.

Food was quite important to Jane because she never had very much of it.

As well as short rations, Jane has to put up with her employer pocketing her rightful commission, and she knew that if she was sacked she would find it very difficult to find another job. Even though she was not married, like Lily, whose husband drank the wages, she was in practise still very vulnerable to men, and also to the judgmental codes of her small town, which blamed her when an upperclass man tried to take advantage. And her salvation ultimately depended in large measure on her friendship with Mrs Briggs: in fact in High Wages, it is the women who have business sense, and the courage to look to the future and to invest in it.

Whipple’s Legacy

The business orientation of the book, I guess, runs through many subsequent fictional streams – women-focused stories of aspiration that, like Whipple’s novels, were bestsellers but sometimes looked down on. My Blackpool grandmother loved to read Catherine Cookson, and I wonder if hers are in that tradition? I am also strongly reminded of Winifred Holtby’s South Riding – although that novel is almost contemporary, and her Sarah Burton is in teaching, not business – and of Maeve Binchy’s entrepreneurial heroines, forging their way through the petty obstacles of small town life, and often being bitterly disappointed in their men.

Meanwhile, like others discovering Whipple, I wonder at Virago’s scorn and am glad Persephone stepped in. I enjoy Whipple’s writing. I enjoy being transported vicariously to a world where people travel by train through fiery industrial landscapes; eat lunch daily in the same cafe, at the same table, with the same companions (and are served calf’s head!); wear alpaca dresses; celebrate the end of the boned corset; pick fights over potted shrimp jars; have passionate encounters in Corporation parks; and display their aspidistras with pride.

Jane Brocket, in the introduction, says that Tidsley may have been Preston.

Thank you so much for the mention! Really enjoyed reading this piece - and I couldn't agree with you more about Noel, I find all the 'business' parts of the book, and Jane's friendships (with Mrs Briggs especially) much more interesting than the romance. I think that Whipple, on the whole, was rather too much of a realist to write very convincing romances. Good marriages, and solid relationships, yes - but that's not quite the same thing!

I detest Persephone's greyness - it must take ages to find the book you want - but they are no worse than the original Whipple editions, of which I inherited several.

I also don't care for shop books, because my mother left school at 14 to work for a dry cleaning firm, and I spent a ghastly ten years working in a tiny High Street shop with my husband. (Working in the Baby Linen department of a large department store when I was still a schoolgirl was "more like it" except at Christmas, which was horrible).

All in all, shop books are not for me, but I strongly recommend trying some of her other work.