Nevil Shute’s Ruined City: a northern town, the Great Depression, and a maverick merchant banker

In my last post I mentioned Ruined City by Shute as an unlikely companion novel to PG Wodehouse’s Big Money, with a very different style but some similar themes. Here follows a closer look at Ruined City. While it’s not my favourite Shute novel (that would be Trustee from the Toolroom) it’s an intriguing look at the time, and directly engages with economic themes in a way few novels do.

First, Nevil Shute. Like Wodehouse, he was an immensely successful and prolific twentieth century writer. His most famous novels are probably A Town Like Alice and On the Beach (which I’ve not had the stomach to read – it’s about nuclear war) and several were filmed. His style could not be more different from Wodehouse. It’s pared back and simple, and his plots proceed in a deceptively simple manner too. He often chooses subjects with a high level of adventure (many are set in wartime) but doesn’t shy away from what might be considered the dry and technical. Shute was an engineer – he wrote 24 novels while working in the aircraft industry – and it shows.

A Shute novel typically involves a very ordinary person who finds themselves in extraordinary circumstances and rises to the challenge, finding reserves of courage, resource and integrity along the way. (In this respect, if no other, reminding me of Tolkien.) In A Town Like Alice, for example, the heroine is a secretary who ends up leading a band of women POWs across Malaya; in Trustee from the Toolroom the hero is an unassuming model-maker.

In Ruined City, the hero is unusual in that he is a member of the elite: a successful merchant banker, Henry Warren, who works in the City of London in Warren Sons and Mortimer, the bank that has belonged to his family for generations. However, Shute cuts him down to size by making him overworked, physically unwell and a cuckold – he is being cheated on by his bored, socialite wife. To reinforce the humiliation, her lover is “a black man” (in fact, a wealthy Arab). I’ll say a bit more about Shute and the thorny subject of race later.

Warren’s response is to ask his wife to move with him to the country and start again: when she chooses divorce, he has a near breakdown and tries to solve it by taking an impromptu walking trip across the North of England. Eventually he collapses at the side of the road and is taken to the hospital at Sharples. He is operated on, and slowly recovers. The hospital staff and patients assume he is unemployed.

Sharples

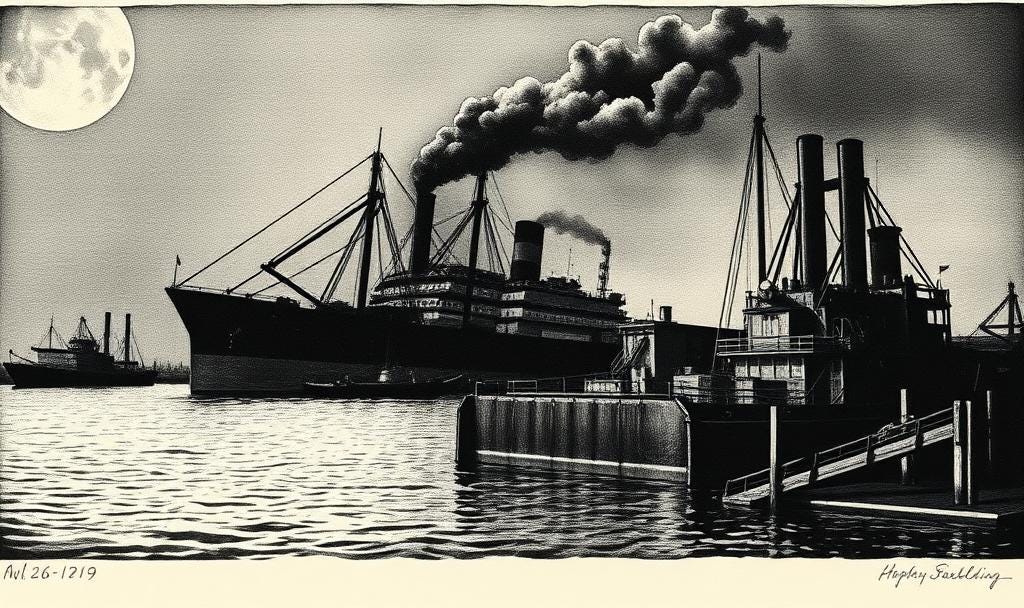

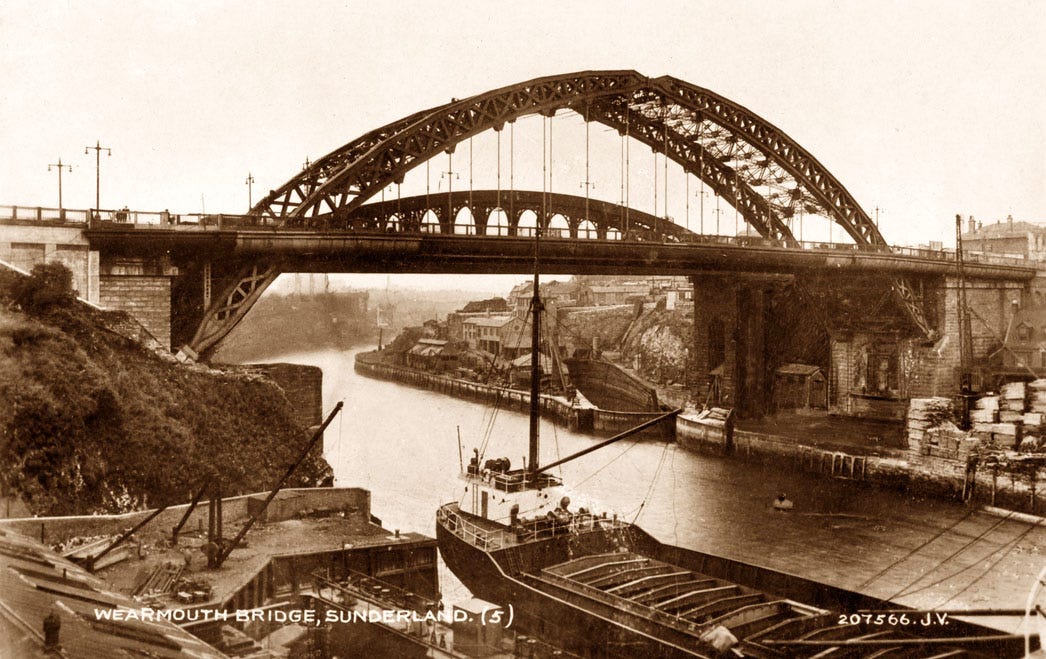

The fictional Sharples is a former industrial town in the North East – think Jarrow or Sunderland. Until recently dominated by shipbuilding (there is a constant refrain from characters in the book of “do you know there were seven destroyers from Sharples at the Battle of Jutland?”) it also once boasted a coal mine and steelworks. But Ruined City was published in 1931 – i.e. during the Great Depression, and in Britain there had already been long years of industrial decline. The shipyards, the mine and the steel works in Sharples have closed. The inhabitants of the once bustling town are now dependent on public assistance (the P.A.C.) –or the dole.

For the wealthy Warren, his time on the public ward at the hospital is a revelation1. Previously he’s had little exposure to the former industrial areas: his life revolves around his London club in the West End, the Square Mile where he does business, European capitals and business trips. Now, he is surrounded by unemployed manual workers. He soon realises the brutal truth: they are dying in unexpectedly high numbers because of years with barely enough to eat.

This stark reality is brought home in a conversation with the Almoner, Miss MacMahon.

“Surely the public assistance rates aren’t so bad as that? [Warren asks] You don’t just have to starve?”

“…The rates are all right, in theory, Mr Warren. You can keep alive and fit on P.A.C. relief–if you happen to have been born an Archangel … if you are careful, and wise, and prudent, you can live on that amount of money fairly well. And you’ve got to be intelligent, and well educated too, and rather selfish. … but you wouldn’t have a penny to spare.”

Miss MacMahon goes on to explain how an impulsive trip to the cinema, a failure at home cooking, or the desire to mark a spouse’s birthday with a small gift, are all likely to lead to financial disaster, hunger and illness. The results are seen in the elevated mortality rates at Sharples hospital, the depressed state of the town and the pallid, apathetic state of its inhabitants.

Warren’s response is interesting, because I think it can be taken to reflect Shute’s own.

“That’s terrible. Because it’s so difficult to change. You can’t expect people in work to pay for people who are idle going to the pictures, or giving presents to their wives. We haven’t reached that stage of socialism yet. And that means there must always be starvation, in a small degree. Because people are human and a little foolish sometimes.”

Nevil Shute was no socialist. After World War II, his disgust with what he saw as the socialist antics of the Labour government led him to emigrate to Australia. His novels reflect his values, in their emphasis on hard work, conscientiousness and individual resourcefulness. Yet his position here is not that different from socialist George Orwell, who wrote in his essays about how while the middle class might judge members of the working class for their choices (sugar and cigarettes over carrots, for example) this was only because fundamentally they did not understand the reality of living in poverty.

Certainly, in the dreadful circumstances of the 1930s, no amount of thrift, positive thinking or hard work was enough. Many of Shute’s contemporaries responded to the economic disasters of the time by embracing extreme new political ideologies – Communism or Fascism; others, like economist John Maynard Keynes, searched for a way to save and humanise capitalism.

For Henry Warren, the disaster of the Great Depression leads to a stark choice. Asked by the surgeon at the hospital if Sharples will revive, he replies that it is too late. Even a return to national prosperity won’t be enough for the decaying town, whose plant is rusting and former workers malnourished and deskilled. “Another war might do it. Nothing less.” (This is far-sighted. It was rearmament which finally solved the mass unemployment created by the Great Depression.) He concludes that while he has wracked his brain for economic opportunities: “I see nothing whatsoever to be done for Sharples.” But then he adds: “Legitimately, that is to say …”

For it does not end there. Warren has always prided himself on his integrity, an important reputational asset in the City. But rather than abandon Sharples, he decides to use his own position illegitimately, to get them on their feet again. He goes to the Baltic state of Laevatia, and by dubious means secures new shipping contracts for the Sharples ship-building yard, which he has bought for a song. He knows the first contracts will make a loss but hopes that, once running, the shipyard will eventually be viable again.

Markets and Mavericks

In a way Warren’s solution is not a million miles from that being propounded at the same time by maverick economist John Maynard Keynes. Keynes, like Warren, could see that the market economy, left to its own devices, was not going to save places like Sharples. Yet many mainstream economists and politicians were still acting as if it would. In Keynes’ view, it made no sense for plant to be rusting, and workers unemployed, their skills and health declining. The difference with Warren is that Keynes advocated a new role for the state in investing the necessary money to get the economy working again. “Anything we can do we can afford,” Keynes claimed: a response to those who advocated an endless, counter-productive, public-spending-slashing austerity.

For Henry Warren, the answer was different: seize the moment, think outside the box and break the rules. And so the respectable merchant banker puts his own reputation and freedom on the line – and almost gets away with it.

Race, nationalism and economics

Back to race. Generally speaking, I’m not one to fret when the mores of another time crop up in its fiction, and distrust the self-righteous condemnations of authors for their failure to meet contemporary ideals of social justice. That said, Ruined City made me more than wince. Warren’s wife (a shallow socialite reminiscent of the cheating Lady Brenda Last in Evelyn Waugh’s Handful of Dust) holds a dinner party where Warren is forced to play host to a Jew (Sir John Cohen) who is trying to rip off a good-hearted young English aristocrat, Lord Cherriton. (It subsequently turns out that the generosity of Lord Cheriton’s mother is what is keeping the hospital at Sharples afloat.) Yet another guest is Prince Ali Said, a wealthy Arab who is sleeping with Warren’s wife. This, in Warren’s eyes, is a far greater humiliation than if she had been sleeping with an Englishman – although Warren reminds himself at least Ali Said has “no negro blood”. Later, Warren visits Visgrad in the fictional Balkan country of Laetivia where he bribes and tricks the corrupt and “swarthy” local politicians for the sake of the salt-of-the-earth folk of Sharples.

“If I had to judge the Visgrad people by the ones I’ve met I’d say they are a lot of sewer rats, but that may not be fair.”

Henry Warren on Laetivia

It’s not entirely one way. Warren acknowledges that his negative impression of Laetavia may be unfair; his long-term confederate, Helmuth, who is Jewish, is decent and honourable as is a Corsican dancer in Visgrad. More interesting to me, though, is whether the distrust and distaste shown for what is different or foreign marks something more than received prejudice. Could it be that Warren – and Shute’s – realisation of the human suffering in Sharples and of the worth of its inhabitants, comes at the expense of other human ties?

In other words, did what seems to be a temporary cessation of the class war, ignite new hostilities instead?

Class and Race

There’s no doubt that before the Great War, many members of the British elites felt more ties with their counterparts abroad than they did with the working classes of their own country. Take John Maynard Keynes again. In the days before World War I, he rarely ventured into the industrial heartlands. His life revolved around Cambridge, London, and country house weekends with wealthy or Bohemian friends. He made frequent trips to the continent. When the Great War ended, he felt deep sympathy with the defeated – whether that was the German-Jewish banker Carl Melchior, with whom he felt he was in a “sort of way” in love, or the starving citizens of Vienna. It wasn’t until the grinding economic slump of the 1920s (Britain was hit earlier than most countries) that he began to pay attention to the British working class. Not that he changed his lifestyle dramatically – but he spent time wrestling with the problems of the cotton industry, visiting mills in the North of England; and made no secret of his sympathy for coal miners in the run-up to the 1926 General Strike. Why, Keynes asked, should the “economic juggernaut” be unleashed on workers who had done nothing to deserve it?

The middle class dislike of the workers was often visceral. George Orwell in his essays recalls how he was brought up to think of the working class as a breed apart; he believed they smelled, regardless of whether they actually did or not. Orwell came to think differently when he spent time with the “down and out” in the 1920s and 30s; he became a socialist, fought in the Spanish Civil War and in 1984 suggests the only hope for the future lies with “the Proles”.

This change in sensibilities had a counterpart in economic policy-making. Keynes, like most of his peers, had always been a strong supporter of free trade. In the 1930s, he abandoned that stance. He shocked other economists by suggesting that goods should be, where possible, “homespun” and his solution to the terrible slumps of capitalism was active state intervention – which itself required a high measure of national autonomy.

Keynes was not nationalistically-inclined by nature. On the contrary, he despised militarism, was largely disinterested in race or other tribal loyalties, and was nostalgic for the Europe of his youth, with its relaxed borders, easily exchangeable currencies and cosmopolitan shared culture. But from the 1930s – even as he fiercely rejected the nationalism of Hitler or British fascist Oswald Mosely – he decided that the national unit was important. It was needed for effective policy-making and he increasingly appreciated its cultural manifestations too. Like George Orwell, and perhaps Neville Shute, English or Britishness as a quality became increasingly attractive rather than parochial.

Perhaps it is one of the great questions of hard times like the 1920s and 30s (and like our own). How do you foster a sense of community and identification in which it is possible to pursue benevolent policies and look out for each other – whether merchant banker or manual labourer – without embracing nationalism and rejecting those outside that community?

Which City?

And finally … I wonder about the title. The novel refers to Sharples as a town. So what is the “Ruined City”? Warren has heard of Sharples before he ended up in a hospital there – when proposals to rescue its shipyards were “hawked round the City … like a vacuum cleaner” many years before. But the City of London preferred to fund foreign ventures and discouraged investors from putting their money into the old industrial areas. Did this focus on short term profit “ruin” it?

Shute’s later novel A Town Like Alice was to continue the economic theme, but that’s a post for another day.

The novel predates the National Health Service. There is quite a bit of discussion of how the hospital at Sharples keeps going, which since the closure of most local industry is mainly through the generosity of a local aristocrat.

What affected him deeply (according to my Dad an aero engineer just a bit younger) was his work on one of two airships R100 and R101; he was on the 'free enterprise' one but when the government sponsored one crashed and burned that was it all over for airships. (They were filled with hydrogen which is highly flammable.) Town Like Alice explicitly celebrates free enterprise as well as engineers and so do other novels to greater or less. On racism and class prejudice in Ruined City, this is the protagonist but not Shute perhaps? As he was very non racist in The Chequer Board notably. EG the story (based on truth) about segregated Southern regiment stationed in English countryside whose officers explained to the local pub that Black soldiers should not be allowed into the pub used by the Whites - and then met a sign excluding white US soldiers from that pub... Alice too is respectful of Aboriginal Australians and also Malay though understandably hostile to Japanese. 'Landfall' has class issues, working class girl with air force officer, and a bit of gender politics, treated sentimentally but without prejudiced attitudes. Ruined City title I took as derived from 'The Waste Land' but may be wrong. Protagonist goes to goal 3 years doesn't he? Having defrauded investors to revive the shipyard. I think it's a story about overcoming class prejudice and the moral decision he then takes. I owe gratitude to Shute: my Dad in late 90s would read and reread his books when he'd lost the ability to read anything else at all.

Thanks for a fascinating post. My father was an engineer and a Nevil Shute fan, with the result that I read On the Beach at an impressionable age and have been haunted by it ever since! I also remember No Highway and discussions about planes crashing. My mother, by the way, worked at the RAE during the war.