Nevil Shute's A Town Like Alice: potboiler or text book in feminist economics?

Potboiler or text book in feminist economics?

They spent that day in a curious mixture of love-making and economic discussion.

A Town Like Alice

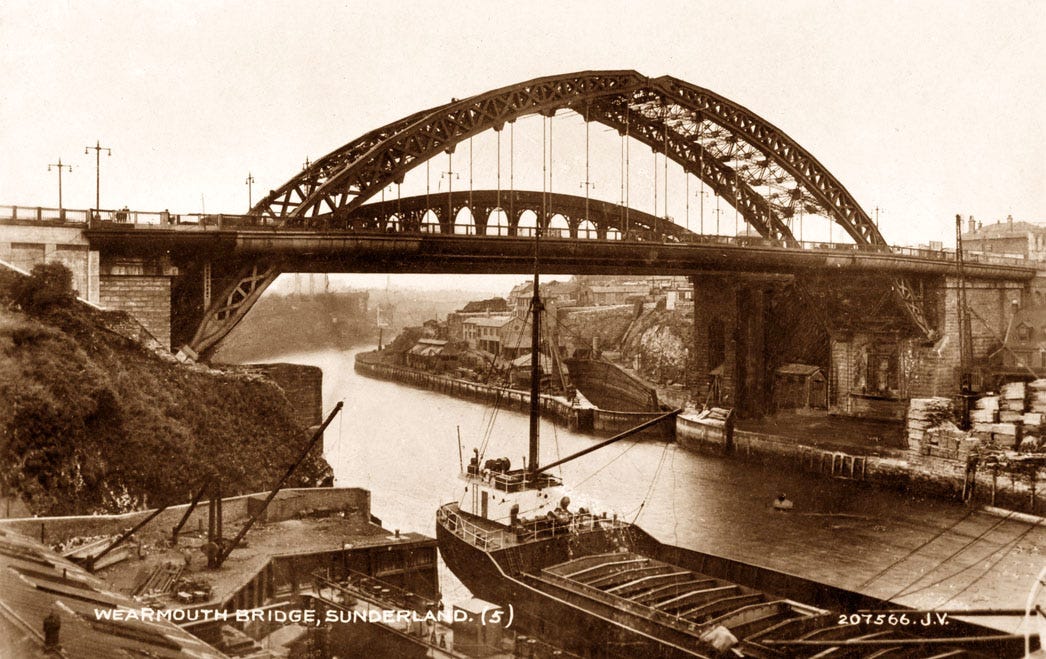

My last post was on Nevil Shute’s Ruined City – a 1931 novel that addressed the between-the-wars slump and the disastrous effect it had on industrial areas of Britain. But in tackling these economic themes, Ruined City was a precursor for a much more famous book: Shute’s bestselling and much loved A Town Like Alice.

A Town Like Alice (1950) is an ambitious story and at first sight very different from Ruined City. For a start, much of it is a World War II story, set in Malaya, and later post war Australia. The protagonists also seem different: Jean Paget is an apparently ordinary secretary in her late twenties, and unlike the middle-aged hero of Ruined City, is in no way part of the financial elite, but lives in a bedsit in suburban Ealing. The novel is narrated by Noel Strachan, a widowed lawyer close to retirement who brings Jean news of an unexpected legacy, then helps her to adjust to her change in fortune.

As she grows close to Noel, Jean tells him her story. Before the war she was a secretary in Malaya, and when the Japanese invaded, she and a group of other women and children were forced to march around the country as prisoners of war. Many died, and Jean became their de facto leader. The survivors eventually settled in a Malay village, where they helped grow rice, and were repatriated to Britain after the war.

When Jean receives her unexpected legacy in 1948, she decides to use her good fortune to help the village women who once helped her. Ultimately this decision will lead her all the way to Australia.

Even in the wartime chapters, there’s a strong interest in the economic, and in the circular transactions needed for survival. Joe Harman, the Australian POW who helps them out, comments on one of his dodgy deals that the women got the soap, their guard a new pair of boots, and the provider of the boots a dollar: “Everybody’s happy and satisfied.” Later, the women work out how they can stop marching by replacing missing labour in the rice fields.

Making Ships, Shoes and Sundaes

While the war story is memorable, the title suggests the later part of the novel is actually more significant. For when she reaches Australia, Jean is faced with a dilemma. She wants to settle down with the man she loves, but she doesn’t think she can bear to live in the place where he lives and works: a small town in the Queensland outback called Willstown. Unlike the lively “Alice” Springs of the title, it is dismal and half-deserted. “There are some places in the outback where one could live a full and happy life,” Jean tells Noel Strachan. “ … But Willstown’s not one of them.”

Jean’s situation echoes that in Ruined City where the banker Henry Warren faces a similar problem. He wants to help the decaying town of Sharples – its inhabitants have shown him kindness and possibly saved his life. Like Jean, he is also drawn romantically to one of the inhabitants. But as a banker, he can see that the situation is unlikely to improve without some kind of dramatic intervention.

The obvious thing for both Henry and Jean is to walk away, give up on Sharples and Willstown and make their lives somewhere else. They have the means to do this and take their partners with them. But it is not in their nature. As with so many Shute protagonists, a quiet and unassuming exterior cloaks determination, grit and a willingness to take risks. They decide to put freedom and fortune on the line.

Henry Warren risks prison and his career rather than abandon Sharples.

Jean Paget sets out to turn Willstown into “a town like Alice”.

“We’ll have to do something about Willstown.”

Jean Paget, A Town Like Alice

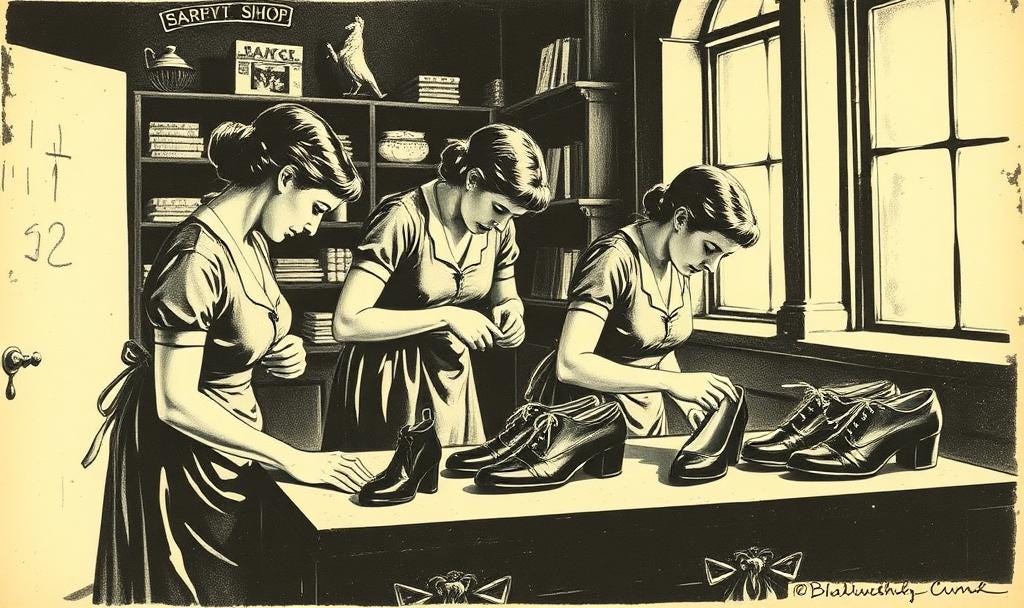

The story of how Jean goes about this is the second half of the book. As a secretary in England, she worked for a leather goods manufacturer. Accordingly, she decides to open a shoe factory in Willstown, using the crocodile skins that are easily sourced locally and employing young girls from the outback who can’t get jobs. Even at this stage, Jean realises the circular nature of an economy, and that the shoe factory is not enough: “I’m going to pay these girls a lot of money … I’ve got to get some of it back.” So she also opens an ice cream parlour, and soon a swimming pool and other businesses. One of the interesting things is that the shoe factory is not especially successful. Later, when Noel Strachan goes out to visit Jean, he worries about its low profitability and if it can be expanded. But the shoe factory is basically a “loss leader” that enables Jean’s other enterprises to prosper. Crucially, by giving economic opportunities to a group which previously left Willstown – young women – it enables the population of the town to increase, as young men (“ringers”) flock to work near them on the surrounding cattle stations, and with resulting young families, the town booms. The shoe workshop may not even be necessary to Willstown in a few years: instead, Jean plans to invest in grocery stores and household goods.

Jean is careful to think about Willstown’s potential before she invests. The high rainfall seems to her a major plus – it means more cattle could be raised, especially if there was a way to dam the rivers, and prevent run-off. When she opens her ice cream parlour, a young man in love with the manageress soon appears – and he has a bulldozer. The dams will be built. Willstown is in a virtuous circle of growth. There’s only one shadow I could detect – a brief reference to the declining number of crocodiles, and so skins for her shoe factory. Development brings its own problems, but they aren’t what this novel is about. Like the smoke and dirt that return to Sharples when the shipyard reopens, the environmental harm is seen as a relatively minor matter in the novels.

Economic Themes

You could argue that while Ruined City is looking at the problem of slump and unemployment – a big issue of the 1920s and especially the 1930s – A Town Like Alice is, twenty years later, looking at the problem of development. How do you create economic growth and prosperity in the first place? Another way of putting this is that Ruined City looks at a previously prosperous community fallen on hard times; A Town Like Alice looks at how to create that kind of community in the first place. There is one more twist though: Willstown was, once upon a time, a gold town. Although that long predates the story, Shute nods to it, by making Jean’s fortune originally derive from Australian gold taken out of the country by her grandfather.

I think it is fitting that the gold that has been taken from those places should come back to them in capital again to make them prosperous.

Noel Strachan, A Town Like Alice

One clear message from both novels is that you can’t rely on free markets. Nevil Shute was emphatically not a socialist1, but if he distrusted governments, nor did he think capitalist institutions, like banks and stock markets, were enough to bring Sharples or Willstown to life. Why? Basically, because these kinds of financial institutions were indifferent to the human and the particular, and liked to play it safe. (Or play it safe in the sense of avoiding places like Willstown or Sharples, even if much other risky and speculative and crash-causing behaviour went on.) In Ruined City Henry Warren knows full well that no City financier will have any truck with Sharples: they would much rather invest in the new light industries, or outside Britain altogether, than risk getting involved in the crumbling industrial areas. In A Town Like Alice, a similar viewpoint is represented by Jean’s cautious lawyer, Noel Strachan. It is his job to conserve her fortune and look to her long term interests: he wonders if he is doing his duty by letting her risk her inheritance in an obscure Australian small town, instead of safe “trustee stocks”.

Ultimately Noel Strachan suppresses his doubts, while Henry Warren decides professional probity isn’t everything. Sometimes financial orthodoxy is not much use. There’s a heroism and a spirit of hope in this which is inspiring: Henry Warren and Jean Paget are both remarkable people, prepared to take a risk. Their decisions are ultimately driven not by rational economic calculus (although both do give that consideration) but by love. The result is both economic and human flourishing.

Yet the question remains: what happens when there is no heroic Henry Warren or Jean Paget? What then?

A Town Like Alice as Feminist Economics?

From the time she had … learnt of her inheritance she had been puzzled, and at times distressed, by the problem of what she was going to do with her life… She was a business girl, accustomed to industry…. Subsconsciously she had been searching, questing, for the last six months, seeking to find something she could really work at.

Chapter 7, A Town Like Alice

Nevil Shute wrote A Town Like Alice – uniquely he says – inspired by real events, the story of a group of women POWs in Sumatra2. Maybe though, he felt it was a bit of a stretch, writing at the age of 50 from the viewpoint of a young woman, and – although he did use a framing device in other novels too – this could be one reason for his using a narrator, the elderly Noel Strachan. He provides a bridge. Shute gave Noel Strachan his own initials, and although Shute himself went to live Australia (unlike the elderly Noel) and had an active life there before his relatively early death, perhaps he did share some of Strachan’s feelings of melancholy as he regarded the dynamic and youthful society around him.

Yet Jean Paget is undoubtedly the protagonist. Seen through Noel Strachan’s eyes she is in some ways an idealised figure – beautiful, serene, almost too good to be true – but Shute also makes her deeply practical. She has “latent business instinct” and revels in discussions about overheads, construction costs and manufacturing techniques. It would be anachronistic to describe Jean as a feminist – and in many ways A Town Like Alice has the values of its time – but there is a very strong element of women using economic means to better their lot. This is true on an individual level – Jean finds deep satisfaction from work and being an entrepreneur – but also collectively.

Jean’s first initiative on inheriting money is to go back to Malaya and build a well for the village women. This is a deeply transformative act: it frees up the women from the labour of going to the spring, gives them a project and meeting place, and subtly changes their relationship with the village men. In Willstown, Jean’s business ventures are also directed towards other women. In part, this is because she knows that there are already economic opportunities for the men, but she is also creating a community in which women and their needs are very visibly to the fore. It’s interesting that in both cases she is giving them space at the very heart of the community. The well is built in the centre of the village, and the adjoining wash-house is designed for and only for use by women. In Willstown (and the other outback towns) women are forbidden the bars, and therefore have no public space to meet and socialise until Jean opens her ice cream parlour.

There’s an interesting contrast between Jean and the men in the novel. Jean inherits from her frail uncle, who seems to have done nothing with his life but inhabit a boarding house and keep budgerigars. Noel Strachan – another elderly gent of cautious habits – spends a lot of time reflecting on whether he is meeting this uncle’s wishes in letting Jean invest her capital. But it is clear that during the uncle’s life, little good was done with the unused fortune. Jean’s grandfather, meanwhile, did not derive the fortune from creating anything new or useful, but from digging up gold in Australia. He then returned to England and died racing in a point-to-point. The men in the novel, even including Jean’s husband, Joe Harman, are notably lacking in vision: it is Jean, often assisted by other women, who sees the possibilities for transformation.

At first I felt woman-as-entrepreneur was an unusual feature for a novel, but there are definitely other novelists, popular and literary, who have gone this route. I wonder if it’s especially attractive where women have few other routes to status or autonomy? Many of Maeve Binchy’s novels feature women finding self-realisation from running a small business, for example. More recently, Lauren Goffman’s historical novel Matrix about medieval nuns focused heavily on the creation of an economically productive community of women. I expect there are other examples too?

Potboiler?

Finally, for anyone who thinks the title a bit provocative, the assessment of A Town Like Alice as potboiler was, according to his daughter, Shute’s own. Apparently he divided his books up into popular money-spinners and the worthwhile. But was his description self-protection - when it comes to what feels like an often heartfelt and genuinely moving novel?

Ronald Turnbull makes some helpful comments on why on my previous post.

It seems he may have misunderstood what occurred, and this group of women weren’t forced to march but transported from camp to camp.

I believe that men have tended to find Trustee in the Toolroom at or near the top of Shute's oeuvre. I always have assumed that for women that place would be reserved for A Town Like Alice. I usually value women's opinions over men's: can the collective wisdom here point to a book that is better regarded? It is often true that what an author considers an entertainment ages better than a meaningful book, but A Town Like Alice scores for me on both counts, but it is not as expertly packaged as Trustee.

Didn't know Substack could generate images for us... I liked Jean Paget in her bush hat, my mother grew up on sheep station in Australia. (My images when not own photos are from Wikipedia or taken in museums where artists died before 1955). A lot of Sstacks are using unsplash whatever that is.) Daughters' grudges? Well 1950s Dads...