Alison Uttley: the classic author more sinned against than sinning

Reading Alison Uttley’s Secret Places on the anniversary of her death

On this day in 1976, the author Alison Uttley died at the age of 91. She must have thought her legacy was assured. She had written many much-loved classics, including the Tudor timeslip Traveller in Time and the Little Grey Rabbit stories. Her relationship with her main publisher, Faber, had lasted decades. Five years before Manchester University had awarded her an Honorary Degree, in recognition of the distinguished literary career of one of their very first female graduates – a pioneer in 1906, in Physics.

Today, Manchester University has a hall of residence for undergraduates named in Alison’s honour. It’s a pleasant surprise that it exists, given the trashing that Uttley’s reputation has received – a vicious character assassination that I have argued is unfair.

Yet so powerful has it been that even someone who might be expected to look more closely – like an equally distinguished woman writer and Uttley childhood fan – accepts it as established truth. Only a few days ago I read writer Margaret Drabble in the Guardian say that Alison Uttley was “not a good mother”.

‘I loved the Alison Uttley stories and was shocked to find in later life that the creator of Little Grey Rabbit was not a good mother and did not like children.’ Margaret Drabble

I shouldn’t have been surprised. A few months earlier, I read in Sam Leith’s much praised book of 2024, Haunted Wood: A History of Childhood Reading, that Uttley was a “cookie full of arsenic”. He also wheeled out a story of a spiky encounter with Enid Blyton – thus helping to perpetuate the myth of a feud with Blyton that has been allowed to define Uttley. (I address the issue of the Blyton feud here.) When I raised these issues with Sam Leith via twitter and pointed him to my substack posts on Uttley, he was most gracious, but there’s no doubt that the poisonous picture of Uttley that originates with her official biography now has its own momentum.

I don’t think Drabble or Leith set out to misrepresent Uttley – on the contrary. But I’d love to find a way of pushing back on the entrenched narrative, beyond the limited platform of my substack. If anyone has any suggestions for how or where, please put them in the comments!

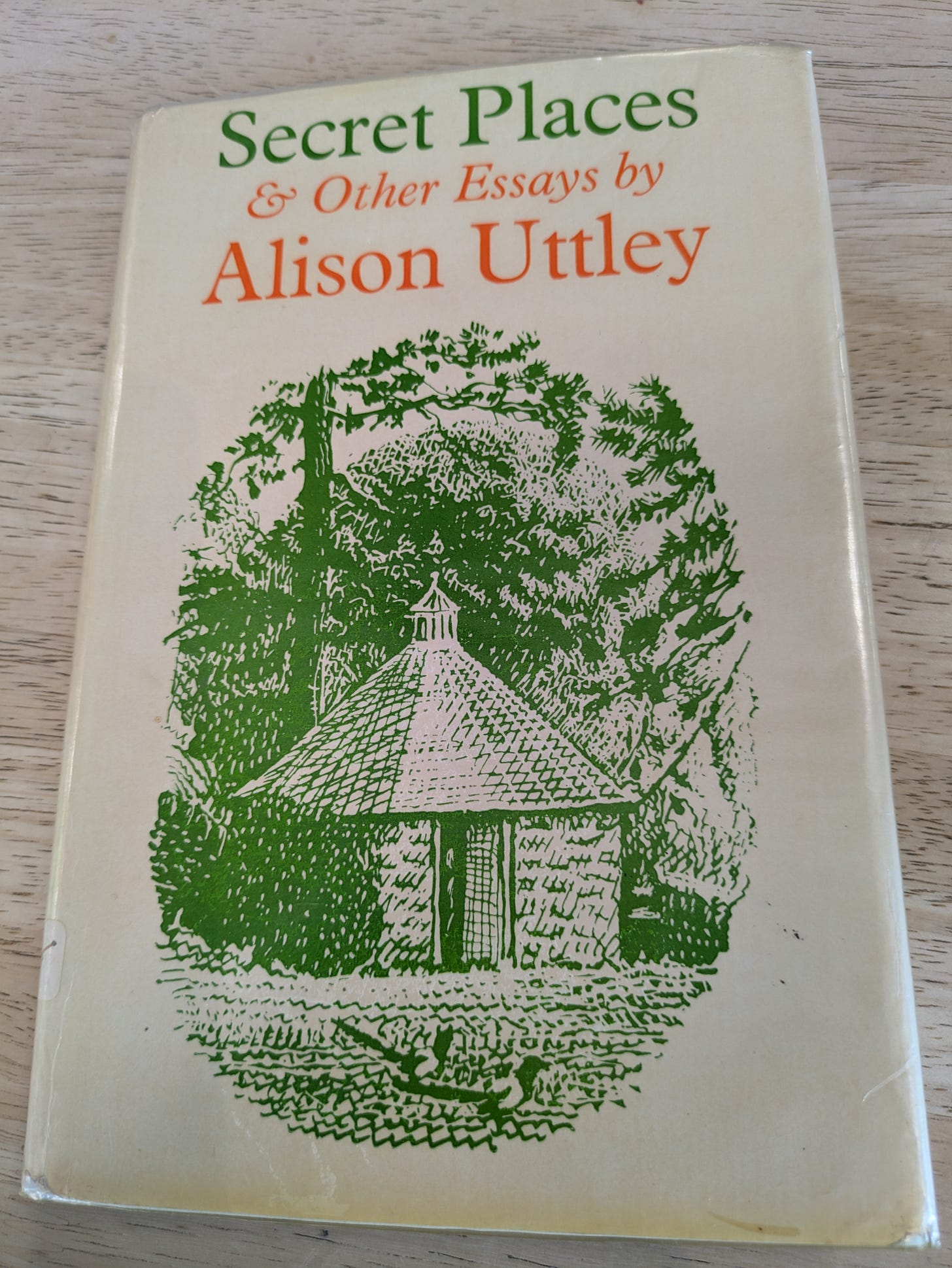

Secret Places

Meanwhile, on the anniversary of her death, I want to celebrate the real Alison Uttley. I have been reading one of her many essay anthologies – long forgotten, but very popular when first published. (They must have been, for Faber published many.) Alison would have been a natural substacker: the essay was her favourite form, and the natural world and incidents from her own life her favourite subjects.

One of the topics in Secret Places is her time at Manchester University studying physics. It’s included in an essay called Falling In Love.

“Radium had been discovered and men talked of Madame Curie and her wonderful work. The lecture room was full of men, a darkened room, and we sat entranced to see a faint living glow of uranium earths, radium and fluorescent bodies. Metals were no longer stable, lead was distintegrating and the world was changing … Matter was alive, it was filled with energy, and atoms were swinging in their orbits, while we tried to measure their speed and find out their properties.”

She conveys brilliantly the sense of excitement. In the same volume, writing on Walter de la Mare, she writes about how she believes science a subject for poetry – “ a realization of the depths of space, the uncharted seas of infinity” – rather than being destructive of the literary imagination, as so many of her contemporaries believed.

She also describes reading de la Mare’s poems to her two-year-old son John.

“I was very lonely, cut off from libraries and from people I knew, my husband was in France, my beloved home far away, and this poem was a light shining … I sang the poem to my little son. It was the first poem he heard except nursery rhymes, and his first words were the chiming ending of the lines.”

I wonder if she read this whether Drabble would think again?

One of the serious claims made against Uttley was that she harboured incestuous passions for her son. Supporting evidence for this are the frequent kisses recorded in her diaries. I argued in an earlier post, Unnatural Passions, that this is a misreading of Alison’s intensely romantic outlook – informed by her own cultural background and late Victorian upbringing. Bluntly, Alison kissed everyone. This is apparent again in Secret Places. In Falling In Love Alison relates her childhood passion for the travelling Irish farm hands who came to her family’s remote farmhouse for the harvest, recalling her love for their “accent, their blarney talk, the music of their whistling, the patter of their feet … as they danced to the stars at night”:

“I held up my face to be kissed by the twins, Patrick and Dominick, who had the Irishmen’s smell about them – the strong aroma of twist and Ireland. Through them I fell in love with Ireland …”

Most likely kisses between a young child and vagrant workers would be discouraged now. But it was a different world.

Even if there is something over-sentimentalized about her for modern tastes, there is also something inspiring in her passionate intensity. Alison was a romantic. Falling in Love goes on to her love of music, science, London, ballet and art. With a jolt I read this passage:

“The dancers were the poetry of motion: the wind blowing, the lightning flashing, the day dying, all were shown to humanity.”

Uttley is writing here about the Russian ballet, which she often went to see in the 1900s when she lived in London, including performances of Fire Bird and The Sleeping Beauty. Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes took London by storm, and its dancers entranced not only a romantic like Alison but also the un-romantic economist and liberal, John Maynard Keynes, who later fell deeply in love with ballerina Lydia Lopokova (who appeared in Firebird). This earth-shattering transformation in his life, a key moment in my novel Mr Keynes’ Revolution, took place while Lydia was performing as the Lilac Fairy in Diaghilev’s version of Tchaikovsky’s classic The Sleeping Beauty1 in 1921, and it is intriguing for me to think that while Maynard Keynes was sitting in the stalls, night after night, falling in love, the young Alison, ten years earlier, had been up in the cheap seats, doing the same.

“I fell in love with Pavlova, whom I went to see on every occasion, for she was an immortal come to earth” Alison Uttley in Secret Places

Secret Places is a glimpse into that odd, intense, passionate and misrepresented writer, Alison Uttley, with her love of scientific discovery, nostalgia for the countryside, and sense of the magical. However much she has fallen into disfavour, I am glad her university remembers her.

My earlier posts on Alison Uttley start here:

The character assassination of writer Alison Uttley: Part 1

This post is a closer look at what happened to the reputation of writer Alison Uttley. While the other writers I discussed previously – Laura Ingalls Wilder and Judith Kerr – both obtained iconic status for their fictions, Uttley’s life and reputation have gone into free fall since the publication of her diaries and authorised biography. Her books are m…

Also on Uttley, Nic Miller has written a beautiful appreciation of Uttley’s sequel to The Country Child, The Farm on the Hill, here.

Diaghilev renamed his production The Sleeping Princess, but it was still the same ballet.

I read a book of essays by Uttley many years ago called I think ‘Wild Honey’ and was inspired by her obvious joy in learning and science, and impressed by the fact she could ‘do’ maths, as I couldn’t! I thought she was an interestingly rounded character.

Thank you so much for these brilliant posts - I love Uttley and visited 'Thackers' recently - A Traveller in Time was one of my favourite books as a child so I was thrilled to be able to visit. I hadn't actually heard about this idea of her as not a nice person until I was doing some research for a post on time-slip novels and came across some articles online so it's good to hear another side to the story.