A Postscript of Roses

A Digest: Iris Murdoch, Keynes, Cambridge scandals, Victorian nurseries ...

As 2024 draws to a close, I thought I’d try one of those digest bits-and-pieces newsletter posts. There’s a bit of a rose theme, having written three recent articles on George Orwell, Maynard Keynes and roses, inspired by Rebecca Solnit’s book, Orwell’s Roses, but it touches on other things too.

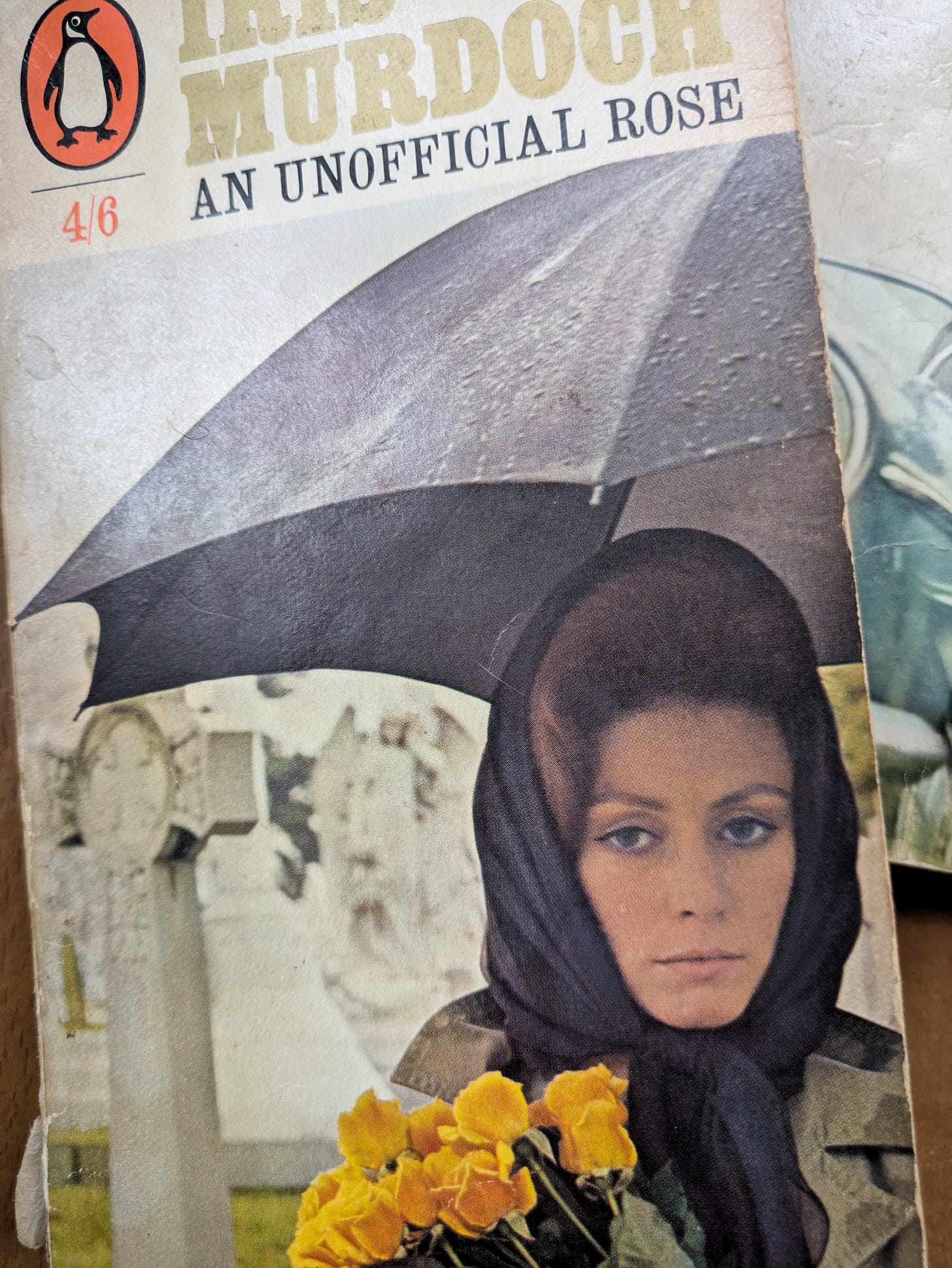

Iris Murdoch and Roses

Reading this enjoyable post about Iris Murdoch from

reminded me that my own favourite Iris Murdoch novel is An Unofficial Rose. I was drawn to Murdoch’s novels as a teen, I think because of their edginess and weird relationships, all of it wrapped up in a kind of intellectual mysteriousness. The prime example was Flight From the Enchanter – in which sort-of heroine Rosa is having a love affair with two Polish brothers at once (incest or relationships approaching it being a common theme in Murdoch) whilst also in a strange dynamic with the mysterious Mischa Fox, her ex-lover and the “Enchanter” from whom she has fled.It’s a cosmopolitan-feeling even exotic book, with cross continental journeys, mysterious millionaires, refugees from recent conflicts and multilingual characters.

By contrast, An Unofficial Rose is more muted and naturalistic and maybe all the better for that. It’s a fairly classic tale of a disintegrating English family, the Peronetts, at the centre of which is the good, but exasperatingly undemanding, Ann (“as shapeless as a bloody dog-rose” her husband comments) plus a stunning Tintoretto picture. It’s rather melancholic, and dwells much on the past and lost opportunities – as well as present ones that may or may not be worth grasping1. Roses are the basis of the Peronetts’ fortunes, but they don’t seem to have brought much happiness.

The title is taken from Rupert Brooke's poem The Old Vicarage, Grantchester:

Unkempt about those hedges blows

An English unofficial rose

which is a celebration of a certain kind of English landscape. An Unofficial Rose itself feels very English (maybe a rather different kind of Englishness to that favoured by Orwell and Keynes – no Agatha Christie references, crumpets or stamp-collecting here, or Brooke for that matter, who was a friend of Keynes) and its maybe not insignificant the most sympathetic character is an Australian. There’s definitely a canker in the roses of the Peronett family.

The Spinning House

I doubt there were ever roses in evidence at the Spinning House. And I think Maynard Keynes, however attached he may have been to Cambridge University, would have strongly disapproved of this bit of its history.

The Spinning House (sounds rather romantic, doesn’t it?) was the prison where for many years the University used to lock up girls and women who dared to walk around the town in the company of undergraduates – or sometimes just for daring to walk about full stop. The suspicion was that they were women of “ill-repute” and their incarceration, of dubious legality, in one case resulted in a woman’s death.

It’s the subject of a book by Caroline Biggs which is discussed in this piece in the Guardian, but I first read about it in a post from

in her Cambridge Ladies’s Dining Society newsletter. Biggs is calling for a memorial plaque, which seems the least the University could do.Keynes and an extra-long bath

I don’t know if they had roses there (quite possibly, as Lydia was more than once leading lady at the Cambridge Arts Theatre across the road) but I was fascinated to read this post yesterday by

who took over the flat where Maynard Keynes and Lydia lived from the mid 1930s. Lydia, as a widow, lived there until 1965 and apparently had Brigitte Bardot cuttings on the wall; the lanky Maynard had installed an extra long bath.Keynes and Roses – Postscript

As I said in my final post about George Orwell and Maynard Keynes, there is a rather odd link between Keynes and roses, in that Keynes’s grandfather, the Victorian entrepreneur John Keynes, helped establish the family fortunes on the back of a successful nursery garden – including the roses he bred. Here is a bit more about him, from Richard Davenport-Hines’ excellent book about his grandson2 .

“he opened a nursery in Salisbury, where he produced dahlias, verbenas and carnations, and hybridized new roses … When the Prince Consort opened the Horticultural Society’s new gardens at South Kensington in 1861, Keynes was a member of the committee that welcomed him.”

The grandfather foreshadowed his famous grandson in several ways: he was a great believer in education, a Liberal, and – unlike Maynard, but like Maynard’s mother, Florence – heavily involved in local politics, becoming Mayor of his town. As Davenport-Hines points out, the triumph of his nursery, built around the garden flowers loved by the middle-classes rather than the aristocracy, reflects the rise to ascendancy of the educated bourgeois class that produced Maynard Keynes.

Some eighty plus years after the grandfather greeted the Prince Consort, Maynard Keynes also welcomed royalty to an opening: in his case, George VI, Queen Elizabeth and the princesses to the ballet at the restored Covent Garden in 1946. It had been a particular project of his in his role at the new Arts Council. The roses may have been artificial, but they had resonance for Keynes: for the production was The Sleeping Beauty, and it was at a production of this ballet almost twenty-five years before that he had fallen in love with his wife, Lydia Lopokova.

Just as that lavish, fairytale production offered an escape from the drabness of between-the-wars Britain, so the 1946 production offered escape and new hope after World War II. It must have been a precious experience for Maynard, who knew that he was unlikely to live long; in fact he suffered heart problems during the performance, which meant that Lydia had to greet the Royal Family in his stead. A few months later, he was dead.

Both 1921 and 1946 productions are discussed in this piece, and here one of the original dancers recalls the 1946 production.

I wonder if any Keynes-bred roses survive? In their place, here is Vanessa Bell, named for Keynes’ close friend, the Bloomsbury artist who suffered the loss of her eldest son in the Spanish Civil War (the same war in which George Orwell was seriously wounded) and now one of the modern day ‘English roses’.

I’d like to thank everyone who read, shared and commented on my posts since I started writing for substack this year. It is a wonderful platform and I find so much to read and think about on here.

Bizarrely some critics at the time – the 1960s – seem to have considered An Unofficial Rose a comedy, which I can’t see at all.

Richard Davenport Hines, The Universal Man: the Seven Faces of Keynes