Who did Virginia Woolf choose for company at Christmas? Of her many Bloomsbury friends and family, it might be a surprise to learn that the answer was often her old friend, the economist (John) Maynard Keynes.

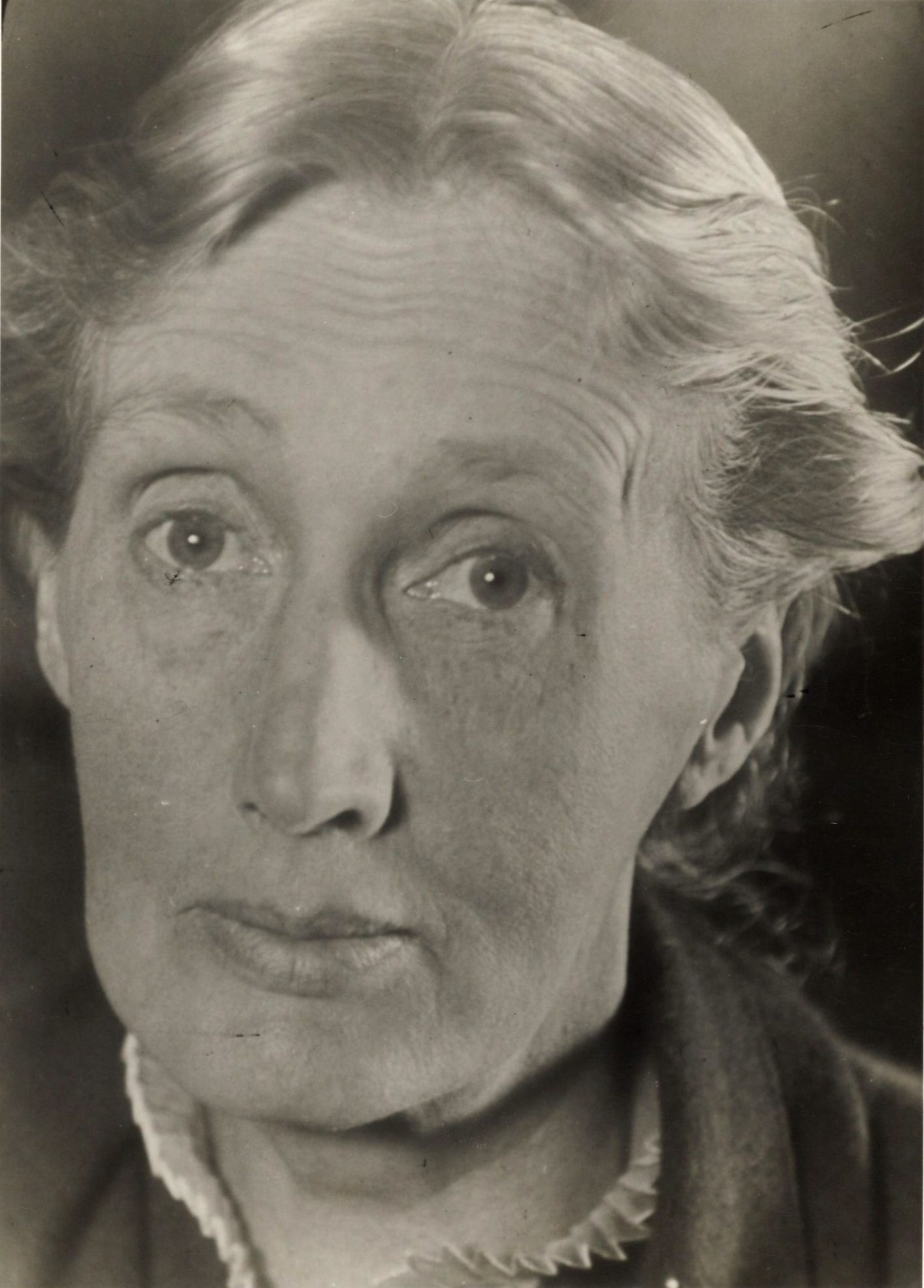

It’s initially surprising because, although Woolf and Keynes went back a long way, they didn’t always get on. Virginia in particular could be vicious about Maynard: ‘… like a gorged seal … sensual, brutal, unimaginative’, she wrote of him in 1920. Maynard meanwhile once got into trouble for leaving Virginia in a state of collapse after a visit to her house at Rodmell: an incident he underplayed to his Bloomsbury friends as being a trivial “touch of the sun”.

“like a gorged seal, double chin, ledge of red lip, little eyes, sensual, brutal, unimaginative”

Virginia Woolf on Maynard Keynes 1920

Nevertheless, the Christmas season usually saw the famous novelist and economist breaking bread together, along with their spouses, Leonard Woolf and Lydia Lopokova. These two giants of Bloomsbury (unquestionably their legacies are the ones that have been most lasting) met either at the Woolfs’ house at Rodmell, near Lewes, or at Tilton, the Sussex farmhouse that was the country home of Maynard and Lydia.

“The Keynes and the Woolfs visited each other regularly at Christmas, mainly, it seems, because they got into the habit of doing so.”

Robert Skidelsky. John Maynard Keynes: The Economist as Saviour p217

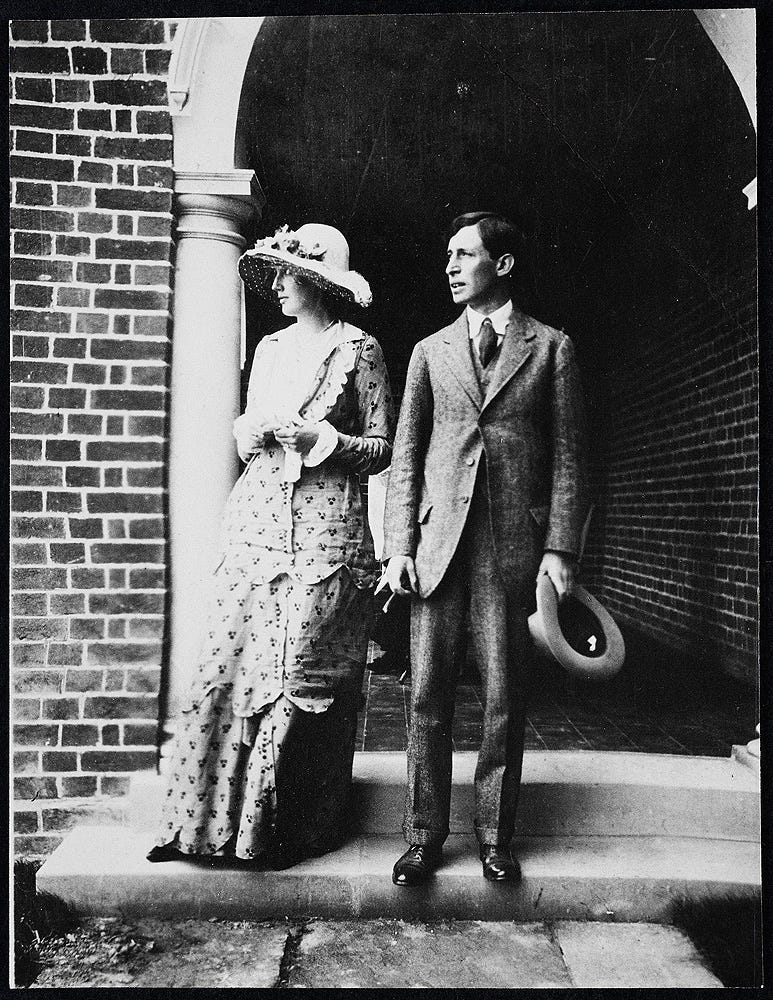

One of Maynard Keynes’s biographers, Robert Skidelsky, suggests it was merely “habit” that sustained the tradition, but this surely overlooks a deeper sympathy. Keynes and Woolf were both original members of the influential Bloomsbury Set and had a long history. They met when Virginia was still Virginia Stephen – the clever and highly strung young woman who set out, with her siblings, to break with the smothering conventions of Victorian society. Maynard was the brilliant Cambridge graduate who had been at university with Virginia’s brother, and a lover to Lytton Strachey – who also proposed marriage to Virginia. In 1911, Virginia and Maynard became house-mates, and two years later Maynard’s brother, Geoffrey, a surgeon, saved her life after she attempted an overdose.

Gratitude doesn’t always breed affection. Sometimes Woolf’s judgments of Maynard, and later of his wife Lydia Lopokova (a Russian ballerina ) were eye-wateringly nasty. In this she was often echoing the rest of Bloomsbury, especially in the years around World War I when his continued employment at Treasury was seen in their eyes as supporting the war effort. Bloomsbury was ready to condemn Keynes as worldly, even as it benefited from that worldliness (Maynard subsidised the Bloomsbury outpost at Charleston, for example, and he arranged Virginia’s husband Leonard’s job at his pet magazine, The Nation). For Virginia, the writer of A Room of One’s Own, his possession of a fellowship at a Cambridge College – the kind of institutional recognition and support she had been denied – may have aggravated her feelings.

Yet time lessened these aggravations. Virginia always admired his intellect. And she was the recipient and recorder in her diary of some of his more profound and revealing observations about philosophy, religion and his underlying values. While Virginia’s sister Vanessa Bell, who had been close friends with Maynard, was almost estranged after his marriage to Lydia, Virginia became steadily warmer and more charitable in her dealings with the couple.

“The two of them were our dearest friends.”

Maynard Keynes on the Woolfs, 1941

On Maynard’s side, there was always a lot less carping and vitriol. Maynard did not spend much time anaylzing his friends in any case: for one thing, he was extremely busy, and as he was not a novelist, he did not have Virginia’s professional interest in dissecting their characters. He was also, perhaps, a different person to most of Bloomsbury. With his interests turned firmly outside towards the world – academically, politically, professionally – he saw family and friends as a comfort, and tolerated their quirks or spikiness. After he died, Clive Bell paid tribute to his affectionate nature.

The last Christmas that Maynard and Virginia spent together was in 1940. In March 1941 Maynard learned of Virginia’s suicide from Leonard when he telephoned to invite the couple to tea. He wrote to his mother Florence: “we have been much upset this weekend by the sad fate of our dear friend Virginia Woolf. Her old troubles came back on her, and she drowned herself last Friday. She had seemed so very well and normal last time we saw her.”

He then recalled how his brother Geoffrey had raced to St Bartholomew’s hospital to fetch a stomach pump all those years ago, before concluding: “I thought she had steered through all that as a result of the devoted care of … Leonard. The two of them were our dearest friends.”

Maynard and Lydia kept inviting Leonard, and after Maynard himself died in 1946, Lydia continued to host Leonard for Christmas. Lydia’s biographer, Judith Mackrell, describes how Leonard would always bring a jar of Rodmell honey. Lydia herself did not like honey, but Maynard had, and so widow and widower kept the tradition.

I stumbled upon this entry from VW's diary dated 24 Sept 1925 and thought of you (and this post):

'Maynard & Lydia came here yesterday-- M. in Tolstoi's blouse & Russian cap of black astrachan--A fair sight, both of them, to meet on the high road! An immense good will & vigour pervades him. She hums in his wake, the great mans wife. But though one could carp, one can also find them very good company, & my heart, in this the autumn of my age, slightly warms to him, whom I've known all these years, so truculently pugnaciously, & unintimately...'

Here's hoping this is a sign of a forthcoming JMK trilogy novel...revolution, dance, legacy? Fingers crossed!