Part One: George and Maynard – How Did Two Old Etonian Scholarship Boys Become Unlikely Twentieth Century Heroes

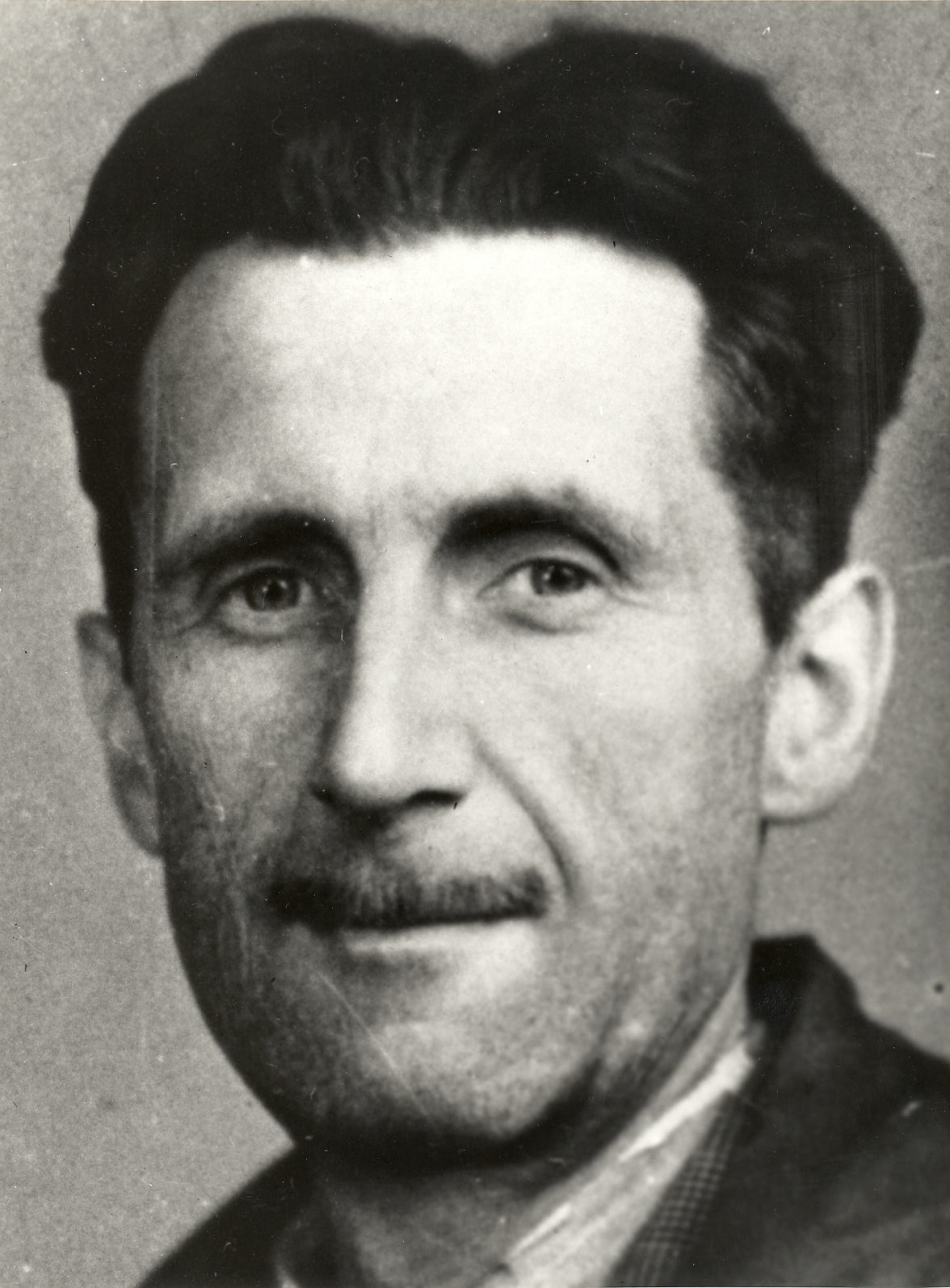

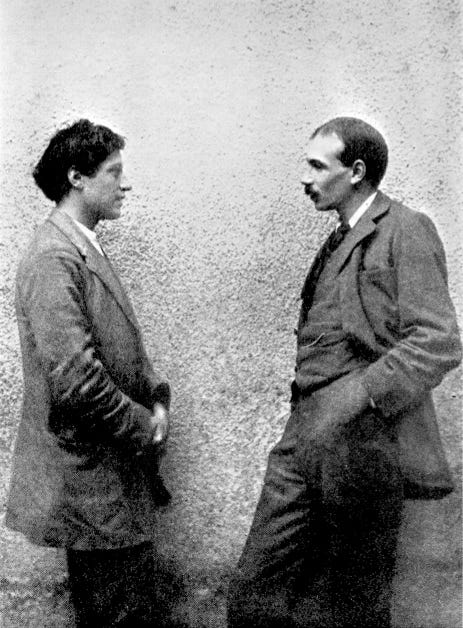

George Orwell and John Maynard Keynes

I started reading Rebecca Solnit’s Orwell’s Roses because I like gardening. I also like George Orwell’s writing, although it is a long time since I have read 1984 or Animal Farm. I find it much harder to read depressing fiction, though, than non-fiction. I can read Orwell’s account of the real disaster that was the Spanish Civil War, Homage to Catalonia, willingly, or his accounts of the terrible poverty in the North of England in the thirties or his other political essays; but the idea of revisiting the dystopian 1984, even though the misery is entirely fictional: no. I’d rather escape into Trollope.

Yet I admire Orwell immensely, I think more than anything else, because of his determination to tell uncomfortable truths, when those around him were equally determined to bury their heads in the sand. It’s truly extraordinary how much of the intellectual Left, committed to their idea of socialism, was prepared to close their eyes tight and simply not see what Stalinism was about: the show trials, the gulags, the famines. (And not just on the Left, at least while the Soviet Union was an ally during World War II.) What did these people have to lose by telling the truth? Yet even the bravest journalists or social reformers – take the outspoken Beatrice and Sidney Webb, for example, who had dedicated their lives to fighting for a better society – seemed unable to accept and acknowledge the reality, choosing instead a wilful blindness. It is this capacity for ideological brainwashing and self deception that Orwell explored so brilliantly in his political novels.

As I read Solnit’s book, which is not a conventional biography but an examination of Orwell’s life through the lens of his love of the natural world (including, unlikely as it seems, gardening!) I found myself more and more startled by the parallels with another intellectual titan of the twentieth century: John Maynard Keynes. I know a lot about Keynes – I’ve researched and written two novels about him – but hadn’t appreciated how the two men’s lives mirror each other: from their education, to their premature deaths, and even their love of the English countryside. There are great differences too, of course – Orwell was never likely to become an Oxbridge don, to be sent to negotiate Britain’s war debt with the Americans, or to be appointed to the House of Lords. But both men were truth-tellers, and both were shaped in different ways by the terrible traumas of the twentieth century – and both tried their damnedest, and with some success, to alter the troubled world for the better.

“Orwellian … a hypocrisy or dishonesty so destructive that it is an assault on truth and thought and rights.” Solnit, Orwell’s Roses

Their legacy has even changed the language: as Solnit puts it, “not many writers become adjectives”. “Orwellian”, unfortunately, is a word we are unlikely to lose any time soon. “Keynesian” is usually attached to “Economics” and reflects Keynes’ vision of capitalism. Keynesians believe that markets can and should be modified and tamed by active state intervention: more specifically that governments have a responsibility to intervene to tackle large scale unemployment; more generally, that an untrammelled capitalism without active intervention is likely to have disastrous economic, social and political results.

“Here are collected … the croakings of a Cassandra who could never influence the course of events in time." Keynes, Essays In Persuasion, 1931

Theirs wasn’t an easy journey. Keynes compared himself to the Ancient Trojan prophetess Cassandra who was fated to accurately foretell disaster, but never be believed. He made the claim in a collection of his political journalism – a form at which Orwell, of course, also excelled. Orwell might have shared his sentiment. Orwell’s book Animal Farm – a fable about the corruption of Communism into totalitarianism – was rejected by numerous publishers in the early 1940s. Orwell did not let that deter him. Keynes, too, found it hard to find outlets for his heretical economic ideas, and being Keynes, did not take no for an answer, and went to the extraordinary lengths of organising a syndicate to buy out a national journal, The Nation, (later the New Statesman), so as to have a platform in the 1920s. Keynes, like Orwell, was also willing to forsake tribal loyalties and when facts warranted it, change his mind.

The Early Lives

How did these twentieth century truth-tellers and heretics begin their lives? How did they achieve such influence? Although separated by twenty years (Keynes was born in 1883, Orwell in 1903) their start in life was similar. Both were the children of middle class families, although Keynes was raised in academic Cambridge, and Orwell (born Eric Blair) mostly in rural Oxfordshire. Orwell was born in India, although his mother brought him back to England at an early age. Neither family were wealthy, and at fourteen both boys entered Eton but only by means of winning a prestigious scholarship.

It’s a bit odd, today, thinking of these maverick intellects spending their early years at the public school famous for nursing the offspring of the establishment. But Keynes, at least, was blissfully happy. He won every academic prize going, performed in plays, debated, and explored friendship and homosexual love. He was good at everything except sport, and being in “College”, the part of the school for scholarship boys, was not adversely effected by the more arrogant and entitled students, present by virtue of their wealth. He made lasting friendships with boys like Daniel Macmillan, who was later to publish one of Keynes’ most momentous works, the Economic Consequences of the Peace. He was even elected to the elitist “Pop”.

Orwell, even more surprisingly, seems to have been moderately happy at Eton. (He is on record as having hated Wellington, the public school he briefly attended first.) He did lots of student journalism and was taught English by writer Aldous Huxley. However, academically “he was unable or unwilling to excel”, in Solnit’s words. So while Keynes gained a scholarship to King’s College, Cambridge where he continued to thrive, Orwell had to find work, and spent the five years after leaving school in the Burmese colonial police – which he hated.

Experiments with Empire

Having been born in India, Orwell may have had a romantic image of the East (although his father worked in the Opium trade, one of the most dreadful manifestations of colonialism). If so, he was soon disenchanted. “I could not go on any longer serving an imperialism which I had come to regard as very largely a racket,” he later wrote. Solnit describes the role of the Imperial Police in Burma as “bullying the locals” and suggests that his subsequent choices to live in poverty in England and France, and chronicle the experience for his first non-fiction book Down and Out in Paris and London, was “an expiation of that colonial phase and an engagement with the classes he had been forced to shun.”

Keynes also entered the service of the British Empire – and disliked the experience. In his case, it was as an official of the India Office. The British Civil Service was assumed to be the automatic destination for clever, highly educated British youth, and Keynes’ family took it for granted that once he had graduated, he would take the demanding entrance exams. He did, successfully, and his reward was a desk in Whitehall at one of the most prestigious government departments, where his first task was to arrange the special export of ten Ayrshire Bulls to Bombay. Within a year he was desperate to leave. He didn’t have Orwell’s reasons to despise imperialism, but he was acutely bored. While Orwell spent five years in the Imperial Police, Keynes managed to escape the India Office in less than two.

It was a bold step for both. Keynes’ father, Neville, was dismayed by his son’s decision. The post in the India Office meant status, a rising salary and security. Keynes threw it over to lecture in economics at Cambridge – an initially informal arrangement paid for by his old mentor, Alfred Marshall. His prospects were uncertain. Fortunately a King’s Fellowship soon followed, and Neville himself also supplemented his son’s income, but as Keynes’ friend Mary Berenson commented, “[Maynard] will never rise to £1000 a year and a KC.”

In fact he did rather more, making a fortune for himself and King’s College, and ending up as Lord Keynes. None of that seemed likely in 1908 however.

Orwell’s decision to ditch the Burma Police in 1927 must have been equally dismaying for his family. He was the same age as Keynes in 1908, but his prospects were far worse. The move plunged him into a hand-to-mouth existence. Orwell embraced poverty over the next few years, going among hop-pickers and down-and-outs and falling seriously ill in a Paris hospital; he also lived in friends’ spare rooms, took odd jobs in bookshops and temporary teaching gigs, while trying all the time to write. He published novels, and accounts of his time among the poor, however his success was meagre. In 1936 he eventually acquired tenancy of a cottage, the attached village shop and a wife, Eileen O’Shaughnessy, but although growing things in the garden gave him enormous joy (this is lovingly detailed by Solnit) it wasn’t a comfortable existence. Eileen reports in a letter to friends how the kitchen was flooded for six weeks in the summer of 1936, with every piece of food going mouldy.

Unlikely Optimists

That both men took this step in their early twenties – throwing over a certain career – speaks to a surprising optimism in their natures. Keynes is often described as an optimist by his biographers – something I used to find odd. Cassandra foresees disaster, after all! Nor is The Economic Consequences of the Peace an optimistic book, and nor were Keynes’ views on capitalism overall (“the economic juggernaut”). Yet however clear-sighted Keynes might be, he always hoped for the best. Famously, he lost money betting on general elections – because he always thought that his choice would somehow triumph, despite the national mood. Keynes was a workaholic and a risk-taker, and it seemed that it was in his nature to look for solutions and never, ever give up.

Orwell, who wrote about the horrors of totalitarianism, seems an even more unlikely optimist. But Solnit does a great job in making the case that he was, and that even 1984 “isn’t a prophecy of doom”. She quotes Margaret Atwood, who claims that the essay on Newspeak at the end of the novel, being written in the past tense, must indicate a future beyond the regime. As with roses in the garden, nothing lasts forever. Solnit sees Orwell’s intense joy in the natural world, in both his life and his novels, as the source of his optimism. Nobody so attuned to the progress of the flowers he had planted, and aware of the changing seasons, could be overtaken by despair.

“The very act of trying to look ahead to discern possibilities and offer warnings is in itself an act of hope.” Octavia Butler – quoted in Orwell’s Roses

Despite their boldness, however, neither Keynes nor Orwell seemed likely to set the world afire in their twenties. Their contemporaries would likely have been astonished to learn that either would coin an adjective! Keynes was admitted to be extremely clever – no less than Bertrand Russell declared that “one took one’s life in one’s hands” when trying to argue with him – but he was still fairly conventional as an economic thinker, even if his personal life among his Bloomsbury friends was not. He could easily have finished his time as a mildly eccentric and obscure, if respected, Cambridge don. Orwell had a handful of good reviews, modest sales and a love of tilling the earth.

For both, it was war – two different wars – that transformed their prospects and shaped their outlook. Two cataclysmic historical events, recognised by both for their destruction and devastation, changed the courses of their lives. My next post will look at Maynard and George: War and Women.

Timeline until 1936, with some selected dates:

On Changing Your Mind

I wrote this a while ago, and published it on Medium. I think it’s one of the best things I’ve written, and I think its message – that the world will not end if we say the wrong thing, make a mistake or even admit that we have changed our mind – is an important one. We are just as polaris…

So interesting, so clever to draw these comparisons, and lots here for me to think about as I start my new project. Thank you. Also, I had forgotten the links between the Macmillan family, Victorian Christian Socialists, right through Daniel De Mendi as friend and publisher of Keynes, to his brother Harold, hardly a Tory at all by the late 1930s. Their grandfather the original Daniel Macmillan would have been very proud of them!

Thank you Michael.